Trump presidency's personnel turmoil stands in stark contrast to the ‘nice guy’ administration of George H. W. Bush

- Written by Eric Stern, Professor of Political Science, College Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity, University at Albany, State University of New York

John Kelly’s resignation as White House chief of staff[1] makes him the latest in a long line of senior officials to leave the Trump administration.

That brings turnover of senior staff[2] at the White House – excluding cabinet-level positions – to 62 percent, which is higher than the past six presidents at the same point in their administrations, according to the Brookings Institution. In addition, no fewer than nine secretaries out of 24 have vacated their cabinet positions.

If Trump has the highest churn of recent presidents, who had the lowest? George H. W. Bush, who died on Nov. 30. His administration had just 25 percent turnover of senior White House staff in the first two years of his presidency. In addition, not a single cabinet member[3] left during that period.

The late Stanford political scientist Alexander George and I wrote about Bush’s management style[4] as part of the 1998 book “Presidential Personality and Performance[5].”

Our analysis of presidents from FDR to Bill Clinton showed that Bush was notable not only for his own foreign policy expertise but for his kinder, gentler approach to managing his team, which led to exceptional collegiality among his staff. And I believe many of his foreign policy achievements came as a result.

Of the advisers in this photo, only Mike Pence remains.

Reuters/Jonathan Ernst[6]

Of the advisers in this photo, only Mike Pence remains.

Reuters/Jonathan Ernst[6]

Impulse control

Given the high turnover among team Trump, you don’t have to look hard to see the impact on America’s foreign policy over the past two years.

Impulsive shifts have been common, such as on policy towards North Korea, when Trump flipped from threatening[7] “fire and fury like the world has never seen” to saying[8] the regime is “no longer a threat” after a summit with the country’s leader – even though little changed.

Other policies were poorly prepared, inadequately coordinated or bungled when they were rolled out. For example, the travel ban[9], which initially attempted to block visitors from seven Muslim-majority countries, caused chaos when it was announced with little discussion[10] among government agencies. And the administration’s zero tolerance immigration policy[11] led to a massive outcry after thousands of children were separated from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border.

In-fighting[12] among advisers and senior staff has been particularly intense, vicious[13] and regularly leaked to the media. In fact, according to conservative Trump critic David Frum, no administration has ever been so prone to leaks[14].

In terms of turnover, the raw stat alone doesn’t fully convey the extent of the problem. In just two years, Trump has had three national security advisers, two White House chiefs of staff, two secretaries of State, two secretaries of Homeland Security and two CIA directors. He’s also had two FBI directors, two National Economic Council directors and soon will have two attorneys general.

It is important to note that while this pattern is certainly striking and concerning – an excessive churn of key officials can be disruptive – it is not unique. Similarly, most modern administrations suffer from internal conflict.

An exception was the first Bush administration.

A kinder, gentler approach

Bush’s national security and foreign policy team was notable not only for its substantial successes and effective policymaking but also for its loyalty, collegiality and relatively limited leaking.

As Bush biographer Jon Meacham put it[15], “The Bush foreign policy team operated with an extraordinary degree of harmony.”

In his entire term, Bush had only one national security adviser and one secretary of defense. His first secretary of state, James Baker, served three years before becoming White House chief of staff.

This harmonious team produced a string of major foreign policy achievements[16]. For example, he presided with prudence and a steady hand over a profoundly turbulent and potentially dangerous time in international affairs, namely the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War.

His team negotiated major reductions[17] in nuclear arms, brought a reunified Germany[18] into NATO over the objections of Russia and European allies and built a broad international coalition[19] to eject Saddam Hussein from Kuwait.

What were the secrets of Bush’s success in leading his national security team? Based on my own research[20] on presidential management styles, managing conflict[21] in foreign policymaking and other research on leadership[22], a number of factors stand out.

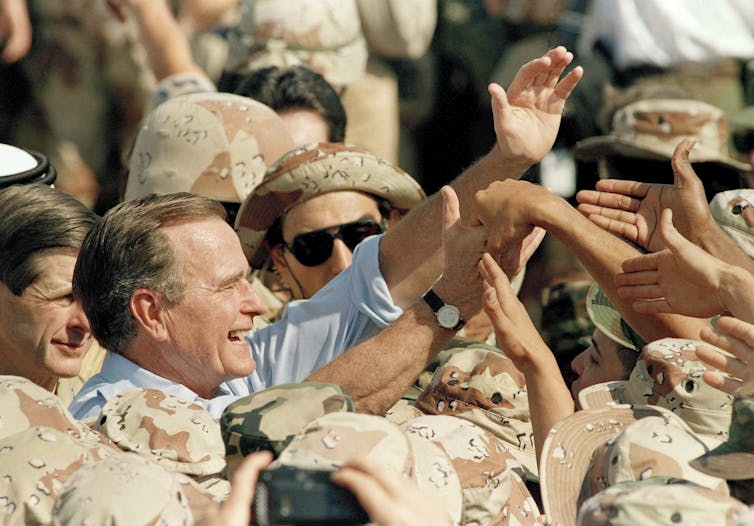

Bush shakes hands with soldiers gathered at a Saudi air base on Nov. 22, 1990.

AP Photo/Bob Daugherty[23]

Bush shakes hands with soldiers gathered at a Saudi air base on Nov. 22, 1990.

AP Photo/Bob Daugherty[23]

Experience and expertise

George H. W. Bush’s career progression – which presidential scholar Tom Preston views as a key variable affecting Bush’s foreign policy performance[24] – prepared him unusually well for the presidency, and especially for leading national security and foreign policymaking.

He served as a naval aviator[25] during World War II, ran an oil company in Texas, served a term in Congress, was an envoy to China, spent a year as CIA director in the Ford administration and worked as Ronald Reagan’s vice president for eight years, all before being elected president in 1988.

Bush was knowledgeable about the issues and comfortable engaging in rough-and-tumble policy debates with his advisers inside and outside of government, as well as with foreign leaders. He respected[26] and was respected by his advisers.

Network and chemistry

Bush developed and maintained a vast social network accumulated throughout his career, built the old-fashioned way through personal relationships. And he drew heavily on this network when he recruited his foreign policy team[27].

In other words, not only was he able to tap people who were highly experienced, well-regarded and competent for key positions, he also had prior personal relationships with many of them. They were both[28] experts and “buddies.” Bush and James Baker shared a relationship that lasted the rest of their lives, with the latter visiting his friend[29] on his deathbed.

These personal ties facilitated candid and critical exchange of information and views, which in turn contributed to effective exploration and solving of national security and foreign policy problems.

Collegiality among the principals

Bush expected his advisers to work together as a team. Competition and policy advocacy would be moderated by norms of collegial behavior and deference to his presidential prerogative to make the final calls[30].

Advisers were encouraged to develop and maintain good working relationships not only with the president but with each other and to refrain from toxic forms of bureaucratic political maneuvering and manipulation not uncommon in Washington[31]. As described in the official State Department history[32], “Although intense policy differences occurred, a collegial approach to foreign policymaking was the norm, especially in the ‘breakfast group’ [that] met weekly to iron out problems that could not be resolved through the bureaucratic channels.”

The professionalism[33] and generally collaborative approach of this team has been noted by many scholars[34].

In addition, open debate was encouraged before a decision was made – but after that, support was expected and generally received[35]. Those who came out on the losing side of a debate received reassurance that they still had the president’s confidence.

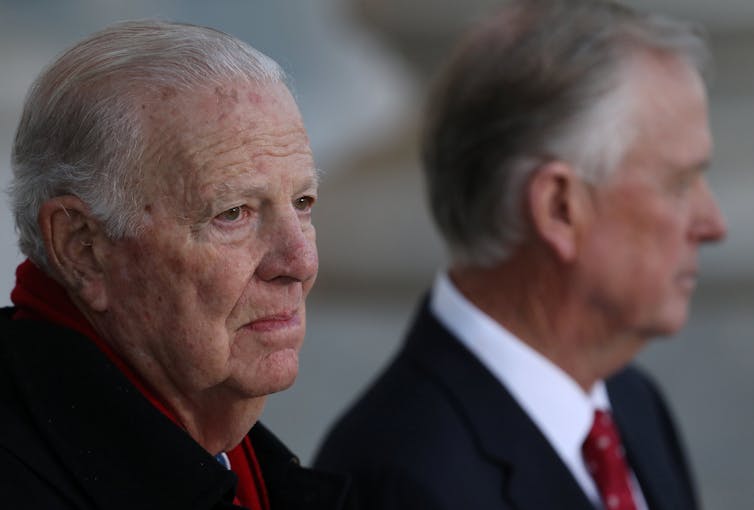

Baker, left, remained Bush’s friend all his life.

Reuters/Win McNamee[36]

Baker, left, remained Bush’s friend all his life.

Reuters/Win McNamee[36]

Gentle leadership and loyalty

In his inaugural address in 1989[37], George Herbert Walker Bush famously defined the goal “to make kinder the face of the nation and gentler the face of the world.”

There are those who believe that nice guys finish last. However, the legacy, leadership style and foreign policy achievements of Bush strongly suggest otherwise.

References

- ^ resignation as White House chief of staff (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ turnover of senior staff (www.brookings.edu)

- ^ not a single cabinet member (minnesota.cbslocal.com)

- ^ Bush’s management style (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ Presidential Personality and Performance (trove.nla.gov.au)

- ^ Reuters/Jonathan Ernst (pictures.reuters.com)

- ^ threatening (www.axios.com)

- ^ saying (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ travel ban (theconversation.com)

- ^ with little discussion (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ zero tolerance immigration policy (theconversation.com)

- ^ In-fighting (www.pbs.org)

- ^ vicious (www.simonandschuster.com)

- ^ prone to leaks (www.harpercollins.com)

- ^ put it (www.penguinrandomhouse.com)

- ^ string of major foreign policy achievements (millercenter.org)

- ^ negotiated major reductions (www.armscontrol.org)

- ^ reunified Germany (www.gsb.stanford.edu)

- ^ built a broad international coalition (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ my own research (scholar.google.com)

- ^ managing conflict (doi.org)

- ^ other research on leadership (www.macmillanihe.com)

- ^ AP Photo/Bob Daugherty (www.apimages.com)

- ^ performance (cup.columbia.edu)

- ^ served as a naval aviator (www.penguinrandomhouse.com)

- ^ He respected (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ he recruited his foreign policy team (www.penguinrandomhouse.com)

- ^ They were both (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ visiting his friend (www.bbc.com)

- ^ presidential prerogative to make the final calls (trove.nla.gov.au)

- ^ not uncommon in Washington (www.press.umich.edu)

- ^ official State Department history (history.state.gov)

- ^ professionalism (www.jstor.org)

- ^ noted by many scholars (cup.columbia.edu)

- ^ generally received (cdn.theconversation.com)

- ^ Reuters/Win McNamee (pictures.reuters.com)

- ^ inaugural address in 1989 (millercenter.org)

Authors: Eric Stern, Professor of Political Science, College Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity, University at Albany, State University of New York