The science, skill – and luck – behind evacuation order calls

- Written by Susan L. Cutter, Carolina Distinguished Professor of Geography and Director Hazards and Vulnerability Research Institute, University of South Carolina

More than 1 million people[1] in the Carolinas were ordered to evacuate days before Hurricane Florence hit landfall.

Government officials order coastal evacuation even when it’s sunny at the beach with not a cloud in the sky and no hint of the ominous threat thousands of miles away other than from satellite images. People who know I study hurricane evacuations[2] have often asked me to explain this curious decision.

In the end, evacuation planning is part science, part skill based on experience, and part luck.

Who makes the call

Evacuations are an example of the precautionary principle: protect people from harm before an event occurs. In the case of hurricanes, the harm is the storm surge[3] – the rise in the sea caused by the hurricane over and above the tides. Storm surge is the cause of most deaths and damages from hurricanes, which is why emergency managers are so concerned about it and go to extreme lengths to get people to evacuate for their own safety.

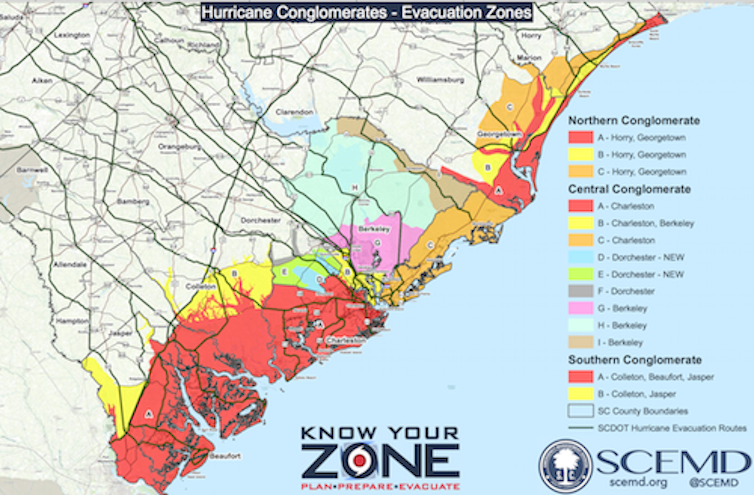

This video on storm surge issued as Hurricane Florence approached underscored the importance of evacuating before the storm.Hurricane planning starts after each hurricane season as city, county and state officials reassess the past season, review operations and update their evacuation zones. In South Carolina, for example, nearly 1.1 million people reside in a designated hurricane evacuation zone[4], but this number does not include seasonal tourists or students enrolled in coastal colleges and universities. In North Carolina, a million people live in storm surge-prone coastal counties, not including seasonal tourists.

In South Carolina, only the governor can issue a mandatory evacuation order. In North Carolina, the governor has that authority as well, but historically has allowed local leaders to make the call. As reported in The Charlotte Observer[5], Gov. Roy Cooper’s office said in a news release: “In North Carolina, when to evacuate starts with a local decision because local officials know their communities and their people best. The governor urges residents to follow evacuation orders issued for their areas.”

South Carolina Emergency Management Division

Gov. Cooper did order a state mandatory evacuation for all barrier islands.

While officials seek input from professionals based on science and experience, the final decision to order an evacuation rests with the governor. Some elected officials do not pass these tests well[6]. Poor handling of the timing and execution of hurricane evacuations can have a political consequences for politicians. For Hurricane Florence, South Carolina’s incumbent governor[7] is up for re-election in a few months.

The timing of the order

Two key science-based factors influence the timing of the evacuation order.

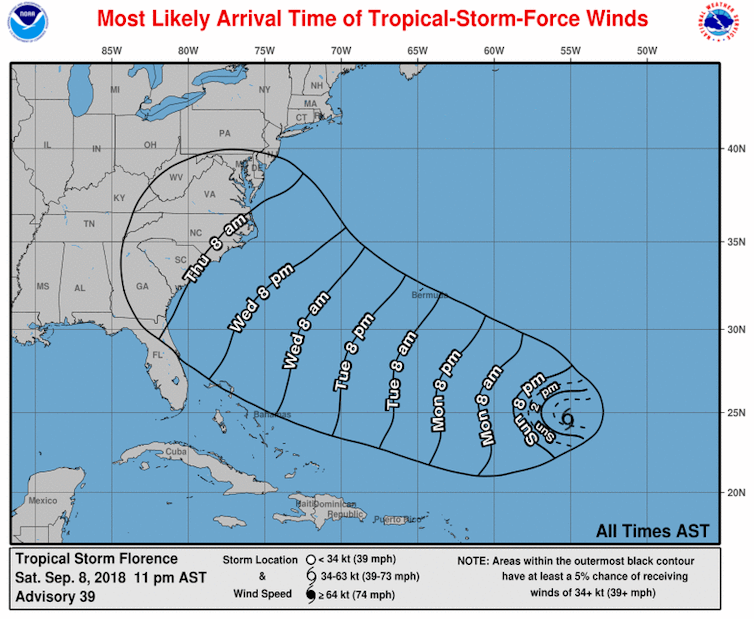

The first is the expected arrival of sustained tropical force winds. Sustained winds in excess of 39 miles per hour impede safe passage over bridges and on roadways, and make it dangerous to travel. Using the five-day projection of tropical force winds[8] in advance of the landfall for Hurricane Florence meant an evacuation needed completion no later than Thursday, Sept. 13, 2018 at 8 a.m. along the coast. There is uncertainty associated with these forecasts[9], despite their being updated regularly with National Hurricane Center advisories. Emergency managers must advise the “go/no-go” decision based on imperfect knowledge of when and where the tropical force winds will arrive.

South Carolina Emergency Management Division

Gov. Cooper did order a state mandatory evacuation for all barrier islands.

While officials seek input from professionals based on science and experience, the final decision to order an evacuation rests with the governor. Some elected officials do not pass these tests well[6]. Poor handling of the timing and execution of hurricane evacuations can have a political consequences for politicians. For Hurricane Florence, South Carolina’s incumbent governor[7] is up for re-election in a few months.

The timing of the order

Two key science-based factors influence the timing of the evacuation order.

The first is the expected arrival of sustained tropical force winds. Sustained winds in excess of 39 miles per hour impede safe passage over bridges and on roadways, and make it dangerous to travel. Using the five-day projection of tropical force winds[8] in advance of the landfall for Hurricane Florence meant an evacuation needed completion no later than Thursday, Sept. 13, 2018 at 8 a.m. along the coast. There is uncertainty associated with these forecasts[9], despite their being updated regularly with National Hurricane Center advisories. Emergency managers must advise the “go/no-go” decision based on imperfect knowledge of when and where the tropical force winds will arrive.

Tropical Winds Arrival Times.

NOAA

On Sept. 10, 2018, there was a mandatory evacuation order issued to 1 million South Carolinians in designated evacuation areas starting at noon the next day, Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2018. Based on updates in the National Hurricane Center’s track forecast cone, the number dropped to 870,000 residents because the three southern counties were no longer in the forecast cone. Officials in North Carolina issued both mandatory and voluntary evacuation orders[10] also starting on Sept. 11, 2018.

The second science-based factor is clearance time – the time elapsed from when the first vehicle enters the road network to when the last vehicle reaches a point of safety. This includes how long it takes to get ready and potential traffic congestion along the way.

Clearance times need three information inputs for modeling: the road network and its capacity; the number of expected cars (based on population numbers plus estimates of tourists); and the behavioral response of residents. Lane reversals (making all lanes of the major evacuation routes one-y.way out from the coast) improve clearance times. However, the major unknown factor is the behavioral response of residents. Will they stay or will they go[11]? In other words, what percentage of the population will get in their cars and evacuate and how quickly will they do this?

A local hurricane evacuation study (HES) provides the data for generating clearance times. Technical documents cover transportation, demographics and the likely behavior of residents[12]. Using data from the HES, clearance time scenarios are modeled using storm strength to generate time estimates by region.

A worst-case scenario would include slow population response, large numbers of tourists, and a major hurricane of Category 3 or higher. In such a situation in South Carolina, for example, it would take 29 hours to evacuate the northern evacuation zones in the Myrtle Beach area and 35 hours for the Charleston region – all of which needs completion before the tropical force winds arrive. In North Carolina, clearance times range from 17-33 hours depending on the coastal location.

What happens when the storm passes?

It is hard to predict the path of hurricanes, and even more so the behavior of people in response to them. There is a lot of uncertainty in the projections of both, which is why you often hear emergency managers say better to be safe than sorry.

Early estimates suggest that in South Carolina, 70-75 percent of the coastal residents evacuated, which is slightly higher than the 64 percent of people who left in Hurricane Matthew[13]. The strength of Hurricane Florence, hurricane-savvy residents, recent experience over the past four years and the understanding of the deadly nature of storm surge all helped coastal South Carolinians to heed the evacuation order and flee from harm on a sunny, balmy day three days before landfall.

The situation in North Carolina is more complicated given how long the storm has been affecting the coast. The initial evacuation estimates are not available as the response is still ongoing. More worrisome are the additional evacuations inland caused by the heavy rainfall and inland flooding[14].

As the storm passes evacuees prepare for the next phase of the evacuation — the return home. Only when local officials say it is safe to return can residents go home. The waiting time for the all clear can take days or weeks, and for anxious evacuees, this is often the most stressful part of the entire evacuation experience.

Tropical Winds Arrival Times.

NOAA

On Sept. 10, 2018, there was a mandatory evacuation order issued to 1 million South Carolinians in designated evacuation areas starting at noon the next day, Tuesday, Sept. 11, 2018. Based on updates in the National Hurricane Center’s track forecast cone, the number dropped to 870,000 residents because the three southern counties were no longer in the forecast cone. Officials in North Carolina issued both mandatory and voluntary evacuation orders[10] also starting on Sept. 11, 2018.

The second science-based factor is clearance time – the time elapsed from when the first vehicle enters the road network to when the last vehicle reaches a point of safety. This includes how long it takes to get ready and potential traffic congestion along the way.

Clearance times need three information inputs for modeling: the road network and its capacity; the number of expected cars (based on population numbers plus estimates of tourists); and the behavioral response of residents. Lane reversals (making all lanes of the major evacuation routes one-y.way out from the coast) improve clearance times. However, the major unknown factor is the behavioral response of residents. Will they stay or will they go[11]? In other words, what percentage of the population will get in their cars and evacuate and how quickly will they do this?

A local hurricane evacuation study (HES) provides the data for generating clearance times. Technical documents cover transportation, demographics and the likely behavior of residents[12]. Using data from the HES, clearance time scenarios are modeled using storm strength to generate time estimates by region.

A worst-case scenario would include slow population response, large numbers of tourists, and a major hurricane of Category 3 or higher. In such a situation in South Carolina, for example, it would take 29 hours to evacuate the northern evacuation zones in the Myrtle Beach area and 35 hours for the Charleston region – all of which needs completion before the tropical force winds arrive. In North Carolina, clearance times range from 17-33 hours depending on the coastal location.

What happens when the storm passes?

It is hard to predict the path of hurricanes, and even more so the behavior of people in response to them. There is a lot of uncertainty in the projections of both, which is why you often hear emergency managers say better to be safe than sorry.

Early estimates suggest that in South Carolina, 70-75 percent of the coastal residents evacuated, which is slightly higher than the 64 percent of people who left in Hurricane Matthew[13]. The strength of Hurricane Florence, hurricane-savvy residents, recent experience over the past four years and the understanding of the deadly nature of storm surge all helped coastal South Carolinians to heed the evacuation order and flee from harm on a sunny, balmy day three days before landfall.

The situation in North Carolina is more complicated given how long the storm has been affecting the coast. The initial evacuation estimates are not available as the response is still ongoing. More worrisome are the additional evacuations inland caused by the heavy rainfall and inland flooding[14].

As the storm passes evacuees prepare for the next phase of the evacuation — the return home. Only when local officials say it is safe to return can residents go home. The waiting time for the all clear can take days or weeks, and for anxious evacuees, this is often the most stressful part of the entire evacuation experience.

References

- ^ 1 million people (www.npr.org)

- ^ I study hurricane evacuations (scholar.google.com)

- ^ storm surge (www.nhc.noaa.gov)

- ^ designated hurricane evacuation zone (coast.noaa.gov)

- ^ The Charlotte Observer (www.charlotteobserver.com)

- ^ pass these tests well (www.postandcourier.com)

- ^ governor (www.thestate.com)

- ^ tropical force winds (www.nhc.noaa.gov)

- ^ forecasts (www.nhc.noaa.gov)

- ^ evacuation orders (patch.com)

- ^ stay or will they go (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ behavior of residents (artsandsciences.sc.edu)

- ^ Hurricane Matthew (journals.plos.org)

- ^ heavy rainfall and inland flooding (theconversation.com)

Authors: Susan L. Cutter, Carolina Distinguished Professor of Geography and Director Hazards and Vulnerability Research Institute, University of South Carolina

Read more http://theconversation.com/the-science-skill-and-luck-behind-evacuation-order-calls-103209